By Beth Dalton, AmeriCorps Vista at A+ Colorado

Twelve school districts in Colorado are seeking new leaders. While we believe that each school district should carefully select the candidate best qualified to serve their community, and that a person’s performance and not his or her race, gender, ethnicity, exceptionalities, sexual orientation, or creed should be the driver for hiring decisions; the staffing of these openings creates a unique opportunity for change. With so many positions open, Colorado could substantially shrink the gender gap at the superintendent level.

Twelve school districts in Colorado are seeking new leaders. While we believe that each school district should carefully select the candidate best qualified to serve their community, and that a person’s performance and not his or her race, gender, ethnicity, exceptionalities, sexual orientation, or creed should be the driver for hiring decisions; the staffing of these openings creates a unique opportunity for change. With so many positions open, Colorado could substantially shrink the gender gap at the superintendent level.

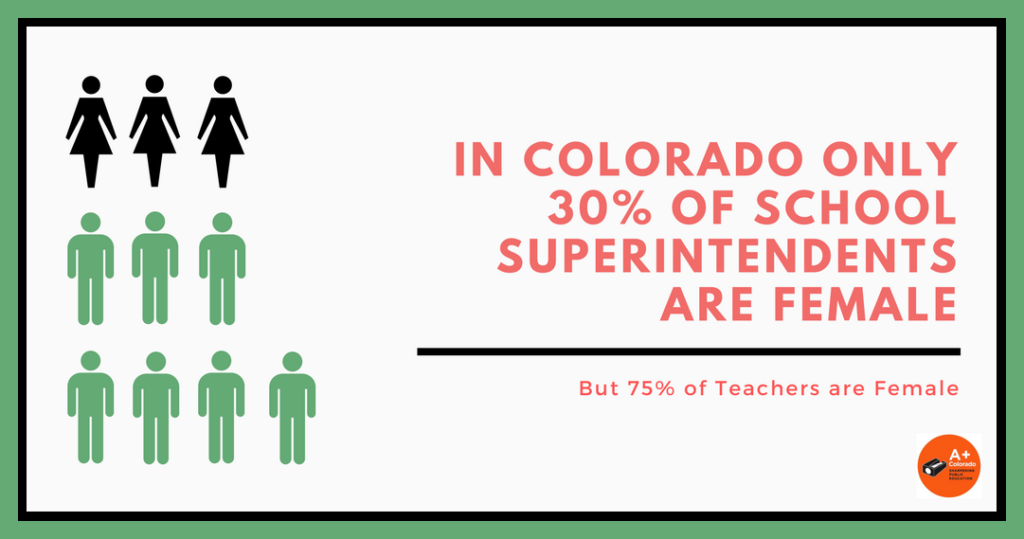

Even though PK-12 education is largely staffed by females, men dominate the superintendent’s office in the nation’s nearly 14,000 districts. Seventy-six percent of teachers nationwide are women; in Colorado 75% of teachers are women. Nationally, 52% of principals and vice principals are women; in Colorado 57% of principals and vice principals are women. With that talent pool, it is startling that women make up only 27% of the superintendents nationwide and 30% of the superintendents in Colorado.

The twelve districts with superintendent positions turning over are:

| District | Gender of Current Superintendent or Interim Superintendent |

| Bayfield School District | Female |

| Boulder Valley School District | Female |

| Cherry Creek School District | Male |

| Cotopaxi (Fremont) RE-3 | Male |

| Douglas County School District | Female |

| Eagle County School District | Female (Interim) |

| Eaton RE-2 School District | Male |

| Elbert County School District C-2 | Male (Interim) |

| Fremont RE-2 School District | Female |

| Sheridan School District 2 | Male |

| Thompson School District R2-J | Male |

While equity concerns alone are enough to take steps to close this gap, are there other reasons why more female superintendents would be good for Colorado?

- Hiring more women may create a more informed representation of elementary education issues. Nationally, nearly 75% of superintendents did not teach at the elementary level before working as a central-office administrator or superintendent, but two-thirds of schools are elementary schools. The School Superintendents Association found that approximately 44% of women superintendents were former elementary teachers. Women superintendents may help to create more pathways for elementary teachers to rise to leadership positions.

- Women often have more experience in curriculum focused roles. In their article, “Necessary but Not Sufficient: The Continuing Inequality between Men and Women in Educational Leadership, Findings from the American Association of School Administrators Mid-Decade Survey”, authors Robinson, Shakeshift, Grogan, and Newcomb write, “Women superintendents (65.2%) are more likely to belong to the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development than men superintendents (46.1%). While, as noted, the number of years spent in teaching is not meaningfully different between women and men, women are more likely to have been a master teacher, a district coordinator, and an assistant superintendent—positions that often indicate a focus on curriculum.” In The Gallup 2017 Survey of K-12 School District Superintendents, superintendents say the top issue facing their district is improving the academic performance of underprepared students. The additional years dealing with curriculum may have better prepared female leaders for this challenge.

- More female superintendents could accelerate the growth of female leadership. Researchers suggest mentorship is key to new superintendents both while they aspire to the superintendency as well as once they achieve the position. Mentoring by race and gender was explored in the AASA 2015 Mid-Decade Survey with 94% of women indicating that they had been mentored. Additionally, this survey found that superintendents most often mentored those like themselves: e.g., white women mentor white women more than any other group; women of color mentor women of color more than any other group, etc. Thus adding even a few female superintendents could build the momentum needed for long-term change.

- Bias against female leaders starts young. It’s important to disrupt that bias. In their report Lean Out: Teen Girls and Leadership Biases Richard Weissbourd and the Making Caring Common Team from Harvard Graduate School of Education found that “Biases often take root early in childhood…. We can work to expose girls and boys to culturally diverse women who model constructive leadership. As parents, we can periodically ask teens whether they think their school—or our family—is modeling gender equality.” Weissbourd and the Making Caring Common Team found both explicit and implicit biases. When asked explicitly who they prefer as political leaders, 23% of girls preferred males while only 8% of girls preferred females, with 69% of girls reporting no preference. Forty percent of boys preferred male to female political leaders and only 4% preferred female political leaders with 56% expressing no preference. The good news is that exposing children to effective women leaders and raising awareness of biases makes a big difference in counteracting bias.

In general, we feel that having an education staff at all levels that represents the students they serve by gender, race and sexual orientation is essential to improving student outcomes and creating an equitable society. In many cases, this means bettering the education hiring pipeline to recruit a more diverse staff. But, in the case of the female gender, there is no pipeline problem. Women make up the majority of entrants in the field of education. So, what could Colorado school leaders do to improve the chances of more women becoming superintendents?

- Ensure that school boards know that the women on their staff are capable leaders – especially in the areas of finance and budget. In their book, Women Leading School Systems, Brunner and Grogan surveyed 1,195 female superintendents and assistant/associate/deputy superintendents and found board member perceptions of females were that they were not good managers and were unqualified to handle budget and finance.

- Offer more co-superintendencies. In her research study “Increasing the Proportion of Female Superintendents in the 21st Century,” Teresa Wallace found that “current female superintendents recommended a co-superintendent job share as a strategy for attracting female superintendent candidates and increasing the proportion of females in the role of superintendent. Participants felt the job to be big enough for two people regardless of the gender of the superintendent.”

- Encourage diverse candidates to apply for the job. In her article, “Stubborn Gender Gap in the Top Job,” Denise Superville quotes “Jazz” Conboy, the general counsel for the New York State Council of School Superintendents. “School boards also have more authority than they might think to attract more female candidates to seek superintendents’ jobs. They can say, ‘we value diversity, we want women applicants, we want minority applicants.”

- Advocate for state-funded yearlong superintendent internships. These would allow many women administrators to gain a solid view of the position. In his article for AASA, Glass recommends this strategy stating that most superintendents derive great satisfaction from their jobs despite the long hours and stressful decisions. The internship may encourage more women to better understand both the tradeoffs and personal satisfaction they may gain from serving as a superintendent.

The role of education as an instrument of social change is widely recognized. Overall, in the U.S. women make 76 cents for every dollar men earn. One of the main reasons for this is that women are underrepresented in the top-earning jobs. If the education community chooses to work on closing the gender pay gap hiring more women to top paying superintendent jobs is essential to accomplishing this aim.

As James Baldwin says, “Children have never been very good at listening to their elders, but they have never failed to imitate them.” If the purpose of education is to prepare students for college, work, and life, then modeling equity in our school systems at all levels is essential to fully prepare our students for a truly demographic, unbiased society.