In order to answer the question, it is important to define what is a public school. There are many ways to answer the question from a legal, political, practice and mission perspective. Some of these are easier to answer than others.

The simple but incomplete answer per Colorado law, a public school “is a school that derives its support, in whole or in part, from moneys raised by a general state, county, or district tax.” Schools that receive public funding are also subject to local, state and federal laws.

Colorado has more than 600 pages of education laws while the recently passed federal Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) is 1061 pages. It is safe to say there are tens of thousands of pages of laws, rules, and guidelines that any public school must follow regardless of whether district-operated, an innovation school or a charter school.

Given the myriad of state and federal education laws and accompanying practices, it is easy to get lost in any analysis of whether a school qualifies as public in good standing.

Even a former Secretary of Education and co-author of ESSA, Senator Lamar Alexander has been confused by the definition of public as was illustrated in comments he made in 2015 congressional testimony.

While the legal definition of what constitutes a “public school” is critical, there are other practice and mission questions that relate to what many of us is believe is central to a public school mission: to educate all for our democracy.

“The tax which will be paid for [the] purpose [of education] is not more than the thousandth part of what will be paid to kings, priests, and nobles who will rise up among us if we leave the people in ignorance. –Thomas Jefferson to George Wythe, 1786.

Thomas Jefferson knew that our prosperity, democracy, and liberty depend upon a thoughtful, educated population. While education is not the only public policy lever needed to create opportunities for everyone, it has been shown to be the most powerful over hundreds of years across races, classes, and genders. Even when it hasn’t fulfilled it’s great purpose, education remains a north star for those who seek to improve their own lives or communities.

I’d argue the definition of public goes well beyond the application of state or federal law. “Public” means to me a mission and practice to serve and educate all students. This nuanced and frankly more complicated definition of what constitutes public often get lost in the shrill debates over charter schools. I believe the answer for many schools as to whether they are “public” requires a continuum from more to less public rather than a simple Yes or No.

As most of us know, public school systems have to take any student that arrives at their doorstep anytime (and should) regardless of whether they went through the school choice process or have special learning needs. Think of the thousands of displaced Puerto Rican families that have sought shelter in Florida this fall and winter.

Thanks to public schools in Florida, these Puerto Rican students had a place to go and learn. The rub often is when kids show up unprepared or at the wrong time of year for schools that are designed only to allow kids to enter at one grade or with certain prior knowledge. I understand that this can be a significant challenge when there is a dual language, IB, Arts or a Montessori program that requires a certain knowledge level to thrive when coming in mid-year or mid-program but there are ways to mitigate some of these challenges. Recently, Denver Public Schools and their charter schools took on this problem and established a new charter contract that requires charter schools to hold back seats and accept students mid-year much like most other DPS schools.

The question of whether a school is public should apply to all schools, district-managed, innovation, charter and yes, even private schools.

I think much can be gleaned through answers to the following three broad categories of questions:

- Is the school open to all students? Can any student attend? Is it a true lottery if there is greater interest than seats? Does the school seek to serve a student population that represents the school’s broader community? Does the school accept students at all grades or just some?

- Does the school serve all of the school’s students well?

- Does the school proactively act to act to narrow the inequality of opportunity for all groups of students that attend the school by income, religion, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation?

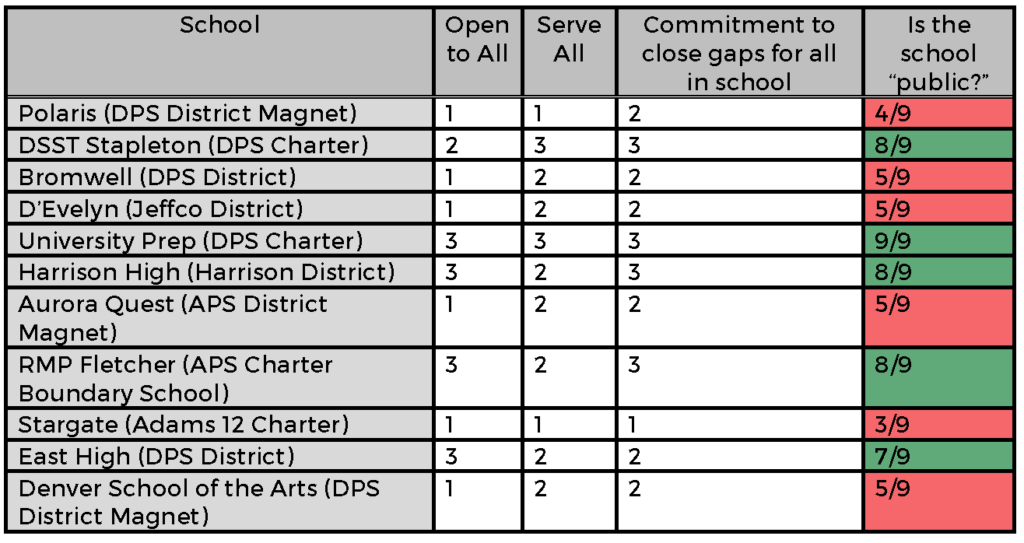

The first two questions are more easily answered while the third question is more complex because it includes a school mission, policies, and practice. I think each of these questions can be answered along a continuum from less to more public. For the sake of this blog, I’ll use a three-point rubric for each question (1=Less Public, 2=Somewhat Public, 3=More Public) and go through a few real school examples of district and charter schools in the Denver Metro Area.

All of the schools on this chart are all good or effective schools as measured by test scores and/or college matriculation. The deeper question that I am asking is the extent that the school commits to and succeeds at serving all students.

In this ranking, the schools above show some fascinating trends. Traditional district public schools that some would defend with the banner of “public” are really not as open as some would think. Other schools, while having a difference of governance type, succeed in broadening and redefining their public commitment to the community they serve. There are any number of district-run or charter schools that may be good but are less “public” than others. And by my definition, any poor performing school is not public because it is not educating its students and serving our communities.

Unfortunately, there are a number of schools, often magnets or neighborhood schools that are unquestionably good but do not serve a student population representative of their communities. I recognize that there is a need sometimes to have specialty schools that target either a particular population or have a focused program like the arts but I also believe it is critical that these schools strive to be public and be placed in the context of a system that supports full access for all to these schools. The lack of feeder schools that target underrepresented populations for selective schools is critical for selective schools to be public. Denver School of the Arts is the classic case for Denver.

There is no question that we need more good schools, but I also believe that we need more good schools with a focused public mission to improve the lives of all students in a geography, particularly those students with the greatest educational needs.

Think about our broader sectors outside of education. Healthcare combines public and private resources for varying degrees of public mission. Infrastructure utilizes private resources to enable public ends. Major corporations are now accountable for public and social good. Think about Google, which used to feel only accountable to shareholders, and now cares about public perception.

Interestingly back in education here in Denver, there are also a few private schools that are legally non-public, yet operate with a public mission. One Denver private school with this mission is Arrupe Jesuit that is open to all, serves low-income Latino kids in NW Denver and provides scholarships to all students. And yes it is a Jesuit school, but it does not require students to be Catholic or to convert. The school mission “teaches the empowerment of the poor and the unleashing of their potential—in action.” It is not a publicly funded school but has a public mission.

The good news is that there appear to be a growing number of publicly funded schools with a clear public mission to serve all students. A powerful example of such a public school is Drew Charter in Atlanta that not only serves all students well within a community but also is integrated into a whole community approach with housing, early childhood, recreation, and parks.

It should also be noted that charter schools in Colorado and most everywhere else in the United States receive less operating funding than district-operated schools and often have far less or little funding for facilities. Charter district funding inequities often make it more challenging for schools to have more of public mission assuming a commitment to serve all students well.

I appreciate the call for schools to be more “public”, but I wish that there was more informed dialogue of what “public” really means in terms of who and how well a student population is served by any public school. The information regarding how “public” the school is should be available to the everyone.

Until we have district, charter schools, school systems and school authorizers committed to being “public” while better serving all students, we can expect education and income gaps in this country to remain the same or grow over time. I welcome feedback and hope this stirs up some debate.

And to circle back to the question of whether charters are public? All of our Colorado charter and district-managed schools are legally public; the question is how “public” is each of our public schools?