Last month, the Denver Public School Board engaged in a conversation with the district leadership about the current state of yellow schools. It was a welcome and long overdue conversation.

In the DPS system red and orange schools are bound to draw the eye of both families, community leaders and DPS leadership. These are our lowest performing schools, sometimes very persistently. They deserve thoughtful and urgent action. However, if DPS is really building a portfolio model, then action and purpose should not be confined to only those at one end of the spectrum.

Currently, DPS operates on a “tiered support framework” that identifies schools for supports and interventions based on current and past performance. The challenge is that the TSF is really an operator-based system. That is, it’s really only for schools the district is running and only to keep them running in the system. It’s not a regulator-based system system, that is managed to ensure the most high quality seats for all students. It’s a valiant effort and one that should continue, for sure. We need DPS and districts to work non-stop on making our schools better places. However, we also need to recognize that that there are current operator biases that cannot be avoided with a system like this.

Many in Denver and nationally are asking the question: what’s next for the portfolio strategy? DPS has passed it’s School Performance Compact that addresses persistently low-performing schools but seems stuck there. Shouldn’t the work of the regulator, the portfolio management of the system, include important functions like addressing schools beyond the red? Like the high school teacher who blames the middle-school teacher and the middle-school teacher who blames the elementary school (as a first grade teacher I often wondered what had happened in Kindergarten), our yellow schools should be among our first line of intervention to ensure schools don’t eventually become persistently low-performing.

The Dilemma

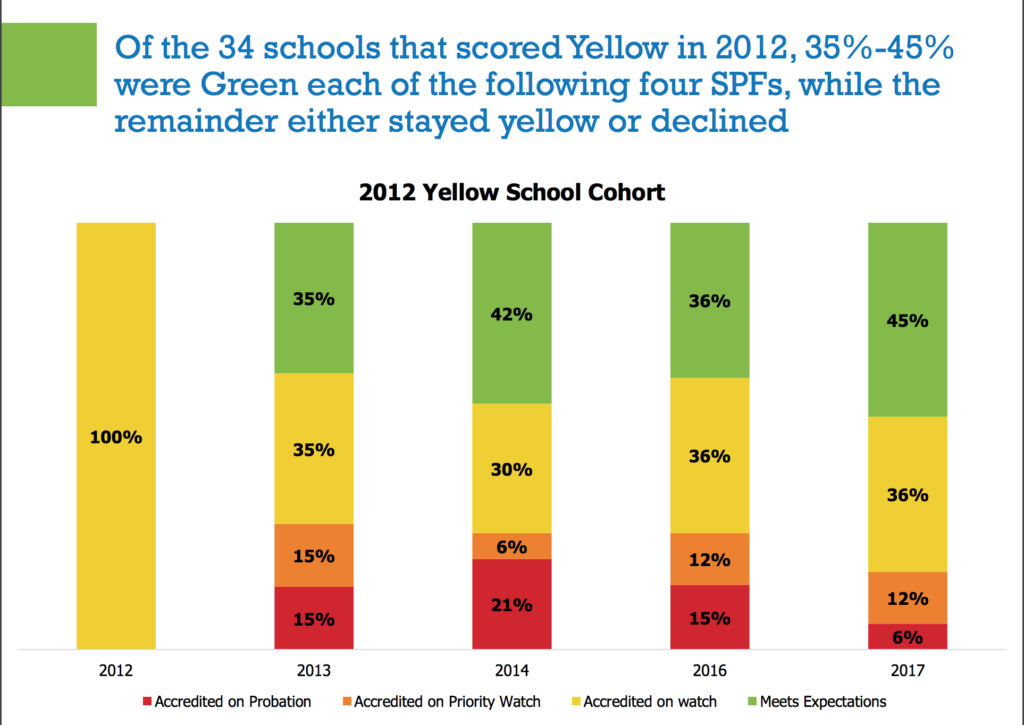

What we learned at the March Board meeting was that about 50% of yellow schools get worse after a few years of being yellow. The other half either stay yellow or move to green (with a very small amount moving to blue). Check out this slide below:

What does that mean? It means that when a school has already slid down to yellow, showing negative trend lines for many kids in the school and not serving nearby families especially well, then despite DPS’ best efforts to improve the school, about 50% continue to fail to meet expectations. Think about that for a second. That’s 26,000 students that we know are already in a precarious school situation. 26,000 students that under current projections, DPS manages to only have a 50% chance to get them to a better situation (…and truthfully, what we know about green schools this past year, it may be significantly more students end up in a same or worse situation).

Why does this happen? There are three primary reasons. First, as humans and managers people are most concerned about urgent, fire-drill like issues. The red and orange schools are assigned those colors for a reason. In portfolio management, we need to think about these schools are critical issues for us to address and they therefore preoccupy most of the district’s bandwidth. Second, the district as an operator managing these schools is enormously risk-averse and pre-occupied by previous investments. The curriculum just rolled out, the principal just hired two years ago who isn’t showing progress but we want to give more time, the new focus on math in third grade, etc. Why wouldn’t they be? Again, that’s a natural thing. Lastly, families follow the cues of the district and the school staff. Families won’t be compelled to exit or speak out unless they have a sense of what is really going on.

Now, if DPS’ track record at getting yellow schools to improve was 60%, 70% or 90%, then we might be having a different conversation. But with the record stuck at 50/50 (or worse), we can’t rely on a coin flip to ensure schools meet our expectations for serving students.

The Opportunity

The School Performance Compact articulated and signaled a major shift in how the Board asked DPS to conduct the business of supporting our most “persistently low-performing schools.” It set clear baselines for what counted as persistently low-performing, set guidelines for family engagement around notification and then articulated a set of policy solutions to ensure dramatic action was taken.

I’d argue the time has come for the DPS Board to amend the School Performance Compact to address a different set of schools: intermittently-performing schools. These would be schools in the yellow band of performance we’ve been talking about but not just any yellow schools. The Board would charge the district with developing a set of criteria that would signal the bright line for what makes an intermittently-performing school. For the sake of discussion, let’s define an intermittently-performing school as one who has been yellow or lower for two years, with an average MGP less than 50.

Schools that meet this criteria would be placed into “intervention-status” by DPS’ Portfolio Office. This is an important process point. A major feature of a robust portfolio office is the severing of operator (district managed schools) and regulator (in this case, the portfolio office). These groups of schools would be mandated to go through one of two different options for consideration. The portfolio office would solicit proposals for both and weigh them against each other with the current processes applying (i.e. a community review board, then Superintendent recommendation and finally Board approval).

Option 1: Jump-Start

To provide the schools with a break in their current operations, one potential could go through a school 6-month redesign. Similar to an approach pioneered by DPS a few years back, the current principal would be temporarily replaced from day-to-day operations by a veteran leader. Over the six-months, the future school leader would lead a community-driven process to redesign the school, align improvement efforts and build new momentum for change. During the course of the year, the incoming school leader would meet with families, community groups and plan for a new opportunity to build change. A leader granted release time, focused on relationship building with families and deeply engaged in school design should be an effective “jump-start” to propel a school to a new level of achievement.

Option 2: Collective Improvement Partnerships With High Performing Schools

In the new moment in our portfolio system, we are required to think fundamentally differently about the intersections between charter, innovation and district schools. If this option is selected, the district would solicit requests for partnerships from high performing schools from across the portfolio to manage a “collective improvement partnership.” These high performing schools would argue that there would be a “positive benefit to the Denver portfolio system” from entering into a deeper partnership with the school. Again, the proposed cross-collaboration would require a long enough runway to deeply engage families and communities. To ensure structural collaboration, an advisory board would be establish to manage the partnership and advise on high-priority issues for the collaboration (such a principal selection, budget, etc.). The Board would consist from the 30% new partner, 30% from the existing school and 40% families/community members.

How would this look in practice? Imagine a high performing blue innovation high school applying for a collective improvement partnership with an intermittently-performing yellow school in a nearby part of the city. This might be particularly beneficial when high performing schools are part of a similar feeder pattern, where those schools could collaborate to better serve all kids in the pipeline. Or imagine a blue Montessori elementary school entering into a collaborative conversion with a yellow elementary school on the entire other side of city. The argument would be that the side of the city with the intermittently-performing school doesn’t have Montessori option for families. Theoretically in time, such cross-collaborations could eventually form innovation networks of their own if they wanted or needed. Another example would be a charter cross-collaboration. Imagine if a charter school with a unique view (language development, cultural identity, college prep) applied for a cross-collaboration to enter into a partnership agreement with a district school. Or a charter school entering into a cross-collaboration with a nearby middle school. They would not be “operating the school” but providing deeper resources and expertise and helping to steer the course their future students might some day take.

Conclusion

Right now for good reason much energy in Denver is focused on persistently low-performing schools. As the Denver community moves toward the next generation of a portfolio model we must broaden our scope and charge.

We must first look at the trajectory of schools and realize that in some cases we need more aggressive intervention earlier in the process. We also must realize that we need to think more creatively about the solutions for the process. If we did all of this, we would be increasing the bandwidth of our portfolio system tremendously. We would be promoting development and cooperation in new and exciting ways, breaking down silos, and sharing lessons between schools and communities. This openness is critical for the system’s success, and most importantly, for our students’ success.